Abstract

Since the mid-twentieth century, elite political behavior in the United States has become much more nationalized. In Congress, for example, within-party geographic cleavages have declined, roll-call voting has become more one-dimensional, and Democrats and Republicans have diverged along this main dimension of national partisan conflict. The existing literature finds that citizens have only weakly and belatedly mimicked elite trends. We show, however, that a different picture emerges if we focus not on individual citizens, but on the aggregate characteristics of geographic constituencies. Using biennial estimates of the economic, racial, and social policy liberalism of the average Democrat and Republican in each state over the past six decades, we demonstrate a surprisingly close correspondence between mass and elite trends. Specifically, we find that: (1) ideological divergence between Democrats and Republicans has widened dramatically within each domain, just as it has in Congress; (2) ideological variation across senators’ partisan subconstituencies is now explained almost completely by party rather than state, closely tracking trends in the Senate; and (3) economic, racial, and social liberalism have become highly correlated across partisan subconstituencies, just as they have across members of Congress. Overall, our findings contradict the reigning consensus that polarization in Congress has proceeded much more rapidly and extensively than polarization in the mass public.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Lest this possibility seem merely hypothetical, consider the classic finding that for much of the twentieth century, Democratic states had more conservative policies than Republican States, despite the fact that within every state Democratic officials were more liberal (Erikson et al. 1989; Caughey et al. 2017).

We obtained Senate roll call data from voteview.com and assigned roll calls to issue domains using the issue codes provided by the Policy Agendas Project (Adler and Wilkerson 2017).

We used the R package MCMCpack (Martin et al. 2011) to estimate the ideal points. To reduce computation time, we sampled 100 economic roll call votes in each congress. For the social and racial ideal points, we used all available roll calls (which always number fewer than 100 per congress). For a discussion of how dynamic IRT estimates differ from DW-NOMINATE scores, see Caughey and Schickler (2016).

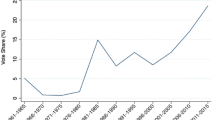

It is important to note that the estimates of intrastate ideological divergence in the Senate plotted in the top panel of Fig. 1 are based on split-party delegations. However, the mix of states with split party delegations has fluctuated over time (Brunell and Grofman 2018). Thus, some of the flux in intrastate ideological divergence in the Senate in Fig. 1 could be due to changes in the mix of states with split-party delegations. We have used two approaches to assess how much changes in the mix of split party delegations affect our analysis in Fig. 1. First, we have replicated the analysis in Fig. 1 separately for Southern and non-Southern states. We find similar patterns across regions, which suggests that changes in the regional mix of split party delegations only have a small effect on our estimates of partisan polarization in the Senate. Second, we have replicated the analysis of the Senate in Fig. 1 using a model that includes fixed effects for each state. This analysis purges the effect of changes in the mix of states with split party delegations by isolating the within-state trends in divergence. This analysis too shows very similar patterns as in Fig. 1.

Trends in intrastate divergence as measured by first-dimension DW-NOMINATE scores look similar to those as measured by our economic ideal points. In particular, according to both measures intrastate divergence in the contemporary Congress is about two standard deviations. This makes sense since the primary content of the first dimension has historically been economic issues (Poole and Rosenthal 2007). The main difference between the two series is that according to DW-NOMINATE, the post-1960 decline in intrastate divergence persisted longer, and the subsequent increase occurred later and less gradually than our economic ideal points imply.

Our preliminary analysis indicates that online surveys, such as the Cooperative Congressional Election Studies, show more polarization and sorting than phone surveys. Thus, we omit online surveys in order to ensure the inter-temporal comparability of our results.

We coded the polarity of questions based on the substantive valence of the question. For example, for economic questions we examined which response option implied a larger scope and size of government. We generally dichotomized multichotomous questions around the middle category.

Our aggregate-level data limit our ability to evaluate how much these developments were driven by changes in the demographic composition of the parties versus changes in individual issue attitudes. We suspect, however, that both factors were at play. We know, for example, that in the 1960s African Americans, who were and continue to be much more racially and economically liberal than whites, became much more likely to identify as Democrats (e.g., Petrocik 1987). This compositional change, along with conservative Southern whites’ more gradual countervailing shift toward the Republican Party (Green et al. 2002, pp. 140–163), likely explains much of the increase in divergence in Southern states, especially on racial issues. On the other hand, we also know that at least some of the growth in polarization is due to individuals’ changing their issue attitudes to match their party’s positions (Levendusky 2009a; Lenz 2012), and thus intrastate divergence is likely also a product of the changing issue attitudes of individuals who remained loyal to one party.

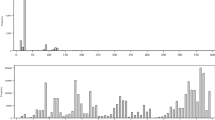

Specifically, within each biennium, we used analysis of variance to decompose variation in conservatism across senators/subconstituencies into between-party and within-party components. The proportion of variation explained by party is simply the between-party sum of squares divided by the total sum of squares.

In addition to being a period of unusually low partisan polarization, especially in presidential politics, the 1950s were also a dry spell for survey questions that tapped into ideological differences over economic policy (see Erskine 1964, pp. 154–155). Both factors may help explain the sudden drop in the explanatory power of party in this decade.

Carmines and Stimson’s analysis was based primarily on a handful of ANES questions. In contrast, we use nearly all available data on public opinion about race during this period from 46 question series across 73 polls.

This too is consistent with the analysis of first- and second-dimension NOMINATE scores in Poole and Rosenthal (2007).

See Hopkins (2018) for a detailed description of how voting patterns in state elections have also nationalized in recent decades.

There is an active debate about how much of the growing geographic concentration of each party’s coalitions is due to residential sorting (Bonica et al. 2017; Mummolo and Nall 2017), cohort effects (Ghitza and Gelman 2014), racial polarization and geographic changes in the distribution of minority populations (Bowler and Segura 2011), or individuals’ switching parties (e.g., Levendusky 2009a; Highton and Kam 2011).

References

Abramowitz, A. I., & Saunders, K. L. (2008). Is polarization a myth? Journal of Politics, 70(2), 542–555.

Adams, G. D. (1997). Abortion: Evidence of an issue evolution. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 718–737.

Adler, E. S., & Wilkerson, J. (2017). Congressional bills project. National Science Foundation grants 880066 and 880061. http://www.congressionalbills.org/download.html.

Aldrich, J. H., Montgomery, J. M., & Sparks, D. B. (2014). Polarization and ideology: Partisan sources of low dimensionality in scaled roll call analyses. Political Analysis, 22(4), 435–456.

Ansolabehere, S., Rodden, J., & Snyder, J. M, Jr. (2008). The strength of issues: Using multiple measures to gauge preference stability, ideological constraint, and issue voting. American Political Science Review, 102(2), 215–232.

Ansolabehere, S., Snyder, J. M, Jr., & Stewart, C, I. I. I. (2001). Candidate positioning in U.S. House elections. American Journal of Political Science, 45(1), 136–159.

Bafumi, J., & Herron, M. C. (2010). Leapfrog representation and extremism: A study of American voters and their members in Congress. American Political Science Review, 104(3), 519–542.

Bonica, A., Rosenthal, H., Blackwood, K., & Rothman, D. J. (2017). Ideological sorting of professionals: Evidence from the geographic and career decisions of physicians. Working paper available at http://as.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu-as/econ/documents/2017-fall/papers_fall-2017/political-economy-fall-2017/Rosenthal_Political_Sorting.pdf.

Bowler, S., & Segura, G. (2011). The future is ours: Minority politics, political behavior, and the multiracial era of American politics. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Broockman, D. E. (2016). Approaches to studying policy representation. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 41(1), 181–215.

Brunell, T. L., & Grofman, B. (2018). Using US Senate delegations from the same state as paired comparisons: Evidence for a Reagan realignment. PS: Political Science and Politics. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000409.

Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1989). Issue evolution: Race and the transformation of American politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Caughey, D., & Schickler, E. (2016). Substance and change in congressional ideology: NOMINATE and its alternatives. Studies in American Political Development, 30(2), 128–146.

Caughey, D., & Warshaw, C. (2015). Dynamic estimation of latent opinion using a hierarchical group-level IRT model. Political Analysis, 23(2), 197–211.

Caughey, D., & Warshaw, C. (2018). Policy preferences and policy change: Dynamic responsiveness in the American states, 1936–2014. American Political Science Review: Pre-published. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000533.

Caughey, D., Xu, Y., & Warshaw, C. (2017). Incremental democracy: The policy effects of partisan control of state government. Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1342–1358.

Clinton, J. D. (2006). Representation in Congress: Constituents and roll calls in the 106th House. Journal of Politics, 68(2), 397–409.

Converse, P. E. (2000). Assessing the capacity of mass electorates. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 331–353.

DeSilver, D. (2018). Split U.S. Senate delegations have become less common in recent years. Pew Research Center. http://pewrsr.ch/2lURzrp.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Dunham, J., Caughey, D., & Warshaw, C. (2016). dgo: Dynamic estimation of group-level opinion. R package version 0.2.3. https://jamesdunham.github.io/dgo/.

Epstein, L. D. (1982). Party confederations and political nationalization. Publius, 12(4), 67–102.

Erikson, R. S., Wright, G. C., & McIver, J. P. (1989). Political parties, public opinion, and state policy in the United States. American Political Science Review, 83(3), 729–750.

Erikson, R. S., Wright, G. C., & McIver, J. P. (2006). Public opinion in the states: A quarter century of change and stability. In J. E. Cohen (Ed.), Public opinion in state politics (pp. 229–253). Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Erskine, H. G. (1964). The polls: Some gauges of conservatism. Public Opinion Quarterly, 28(1), 154–168.

Feinstein, B. D., & Schickler, E. (2008). Platforms and partners: The civil rights realignment reconsidered. Studies in American Political Development, 22(1), 1–31.

Fenno, R. F. (1978). Home style: House members in their districts. Boston: Longman Publishing Group Harlow.

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J., & Pope, J. C. (2005). Culture war?. New York: Pearson Longman.

Fowler, A., & Hall, A. B. (2016). The elusive quest for convergence. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 11(1), 131–149.

Fowler, A., & Hall, A. B. (2017). Long-term consequences of election results. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 351–372.

Ghitza, Y., & Gelman, A. (2014). The great society, Reagan’s revolution, and generations of presidential voting. Unpublished working paper available at http://www.stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/research/unpublished/cohort_voting_20140605.pdf.

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan hearts and minds: Political parties and the social identities of voters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Grofman, B. (2004). Downs and two-party convergence. Annual Review of Political Science, 7, 25–46.

Highton, B., & Kam, C. D. (2011). The long-term dynamics of partisanship and issue orientations. Journal of Politics, 73(1), 202–215.

Hill, S. J., & Tausanovitch, C. (2015). A disconnect in representation? Comparison of trends in congressional and public polarization. Journal of Politics, 77(4), 1058–1075.

Hopkins, D. (2018). The increasingly United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hopkins, D. J., & Schickler, E. (2016). The nationalization of U.S. political parties, 1932–2014. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia, PA, September 3.

Jacobson, G. C. (2012). The electoral origins of polarized politics: Evidence from the 2010 Cooperative Congressional Election Study. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(12), 1612–1630.

Jessee, S. A. (2009). Spatial voting in the 2004 presidential election. American Political Science Review, 103(1), 59–81.

Key, V. O, Jr. (1964). Politics, parties & pressure groups. New York: Crowell.

Layman, G. C., & Carsey, T. M. (2002). Party polarization and ‘conflict extension’ in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 46(4), 786–802.

Layman, G. C., Carsey, T. M., & Horowitz, J. M. (2006). Party polarization in American politics: Characteristics, causes, and consequences. Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 83–110.

Lee, D. S., Moretti, E., & Butler, M. J. (2004). Do voters affect or elect policies? Evidence from the U.S. House. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 807–859.

Lenz, G. (2012). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ performance and policies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S. (2009a). The microfoundations of mass polarization. Political Analysis, 17, 162–176.

Levendusky, M. S. (2009b). The partisan sort: How liberals became Democrats and conservatives became Republicans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levitt, S. D. (1996). How do senators vote? Disentangling the role of voter preferences, party affiliation, and senator ideology. American Economic Review, 86(3), 425–441.

Lunch, W. M. (1987). The nationalization of American politics. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Martin, A. D., & Quinn, K. M. (2002). Dynamic ideal point estimation via Markov chain Monte Carlo for the U.S. Supreme Court, 1953–1999. Political Analysis, 10(2), 134–153.

Martin, A. D., Quinn, K. M., & Park, J. H. (2011). MCMCpack: Markov chain Monte Carlo in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 42(9), 1–21.

McCarty, N., Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2009). Does gerrymandering cause polarization? American Journal of Political Science, 53(3), 666–680.

Mickey, R. W. (2015). Paths out of Dixie: The democratization of authoritarian enclaves in America’s Deep South. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mummolo, J., & Nall, C. (2017). Why partisans do not sort: The constraints on political segregation. The Journal of Politics, 79(1), 45–59.

Paddock, J. (1992). Inter-party ideological differences in eleven state parties: 1956–1980. Western Political Quarterly, 45(3), 751–760.

Peress, M. (2013). Candidate positioning and responsiveness to constituent opinion in the U.S. House of Representatives. Public Choice, 156(1–2), 77–94.

Petrocik, J. R. (1987). Realignment: New party coalitions and the nationalization of the South. Journal of Politics, 49(2), 347–375.

Poole, K. T. (1998). Recovering a basic space from a set of issue scales. American Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 954–993.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (1984). The polarization of American politics. Journal of Politics, 46(4), 1061–1079.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (1985). A spatial model for legislative roll call analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 29(2), 357–384.

Poole, K. T., & Rosenthal, H. (2007). Ideology & Congress. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Schattschneider, E. E. (1942). Party government. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Schickler, E. (2013). New Deal liberalism and racial liberalism in the mass public, 1937–1968. Perspectives on Politics, 11(1), 75–98.

Shafer, B. E., & Claggett, W. J. M. (1995). The two majorities: The issue context of modern American politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press Press.

Shor, B., & McCarty, N. (2011). The ideological mapping of American legislatures. American Political Science Review, 105(3), 530–551.

Stimson, J. A. (2015). Tides of consent: How public opinion shapes American politics (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tausanovitch, C., & Warshaw, C. (2013). Measuring constituent policy preferences in Congress, state legislatures and cities. Journal of Politics, 75(2), 330–342.

Treier, S., & Hillygus, D. S. (2009). The nature of political ideology in the contemporary electorate. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(4), 679–703.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for helpful conversations with Chris Tausanovitch and for feedback from Howard Rosenthal and participants at the 2016 ASU Goldwater Conference on Campaigns, Elections and Representation and the 2016 Midwest Political Science Association and American Political Science Association conferences. We appreciate the research assistance of Melissa Meek, Rob Pressel, Stephen Brown, Alex Copulsky, Kelly Alexander, Aneesh Anand, Tiffany Chung, Emma Frank, Joseff Kolman, Mathew Peterson, Charlotte Swasey, Lauren Ullmann, Amy Wickett, Julie Kim, Julia Han, Olivia H. Zhao, Mustafa Ben, Szabolcs Kiss, and Dylan DiGiacomo-Stumm. Upon publication, the data and code necessary to replicate the analysis in this article will be posted in the Harvard Dataverse.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caughey, D., Dunham, J. & Warshaw, C. The ideological nationalization of partisan subconstituencies in the American States. Public Choice 176, 133–151 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0543-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-0543-3